Mondauk Common:

Michael-Patrick Harrington's Blog

Rolling Stone: How the Christian Right Helped Foment Insurrection

Excellent piece from Rolling Stone. Right on the money.

Duran Duran cover Bowie

Finally a video for Duran Duran’s cover of David Bowie’s “Five Years,” accompanied by Mike Garson, the pianist for Bowie’s Spiders from Mars.

Kenobi

Oh my! A new Star Wars mini-series is coming…Kenobi.

More from the Overdriver Duo

Overdriver Duo

I’m not a Dire Straits fan, but I like this duo’s video.

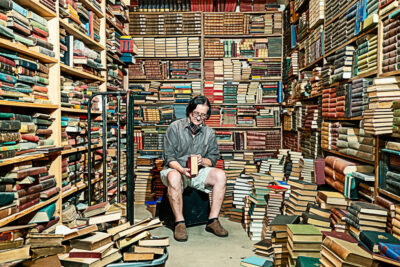

Washington’s Secret to the Perfect Zoom Bookshelf? Buy It Wholesale.

From POLITICO.COM – POLITICO MAGAZINE

By ASHLEY FETTERS

12/26/2020 06:30 AM EST

Ashley Fetters is a feature reporter at the Washington Post.

In a place like Washington—small, interconnected, erudite, gossipy—being well-read can create certain advantages. So, too, can seeming well-read. The “Washington bookshelf” is almost a phenomenon in itself, whether in a hotel library, at a think tank office or on the walls behind the cocktail bar at a Georgetown house.

And, as with nearly any other demand of busy people and organizations, it can be conjured up wholesale, for a fee.

Books by the Foot, a service run by the Maryland-based bookseller Wonder Book, has become a go-to curator of Washington bookshelves, offering precisely what its name sounds like it does. As retro as a shelf of books might seem in an era of flat-panel screens, Books by the Foot has thrived through Democratic and Republican administrations, including that of the book-averse Donald Trump. And this year, the company has seen a twist: When the coronavirus pandemic arrived, Books by the Foot had to adapt to a downturn in office- and hotel-decor business—and an uptick in home-office Zoom backdrops for the talking-head class.

The Wonder Book staff doesn’t pry too much into which objective a particular client is after. If an order were to come in for, say, 12 feet of books about politics, specifically with a progressive or liberal tilt—as one did in August—Wonder Book’s manager, Jessica Bowman, would simply send one of her more politics-savvy staffers to the enormous box labeled “Politically Incorrect” (the name of Books by the Foot’s politics package) to select about 120 books by authors like Hillary Clinton, Bill Maher, Al Franken and Bob Woodward. The books would then be “staged,” or arranged with the same care a florist might extend to a bouquet of flowers, on a library cart; double-checked by a second staffer; and then shipped off to the residence or commercial space where they would eventually be shelved and displayed (or shelved and taken down to read).

Only sometimes do Bowman and Wonder Book President Chuck Roberts know the real identity of the person whose home or project they’ve outfitted: “When we work with certain designers, I pretty much already know it’s going to be either an A-list movie or an A-list client. They always order under some code name,” Bowman says. “They’re very secretive.”

Roberts opened the first of Wonder Book’s three locations in 1980, but Books by the Foot began with the dawn of the internet in the late 1990s. A lover of books who professes to never want to see them destroyed, he described the service as a way to make lemonade out of lemons; in this case, the lemons are used books, overstock books from publishers or booksellers, and other books that have become either too common or too obscure to be appealing to readers or collectors. “Pretty much every book you see on Books by the Foot [is a book] whose only other option would be oblivion,” Roberts says.

Located in Frederick, Wonder Book’s 3-acre warehouse full of 4 million books is a short jaunt from the nation‘s capital. While the company ships nationally, it gets a hefty portion of its business from major cities including Washington. And, over the past two decades, Books by the Foot’s books-as-decor designs have become a fixture in the world of American politics, filling local appetite for books as status symbols, objects with the power to silently confer taste, intellect, sophistication or ideology upon the places they’re displayed or the people who own them.

Wonder Book’s designs have been featured in a number of locations in and around D.C. According to Roberts, The Madison hotel once purchased 19th-century American history texts to use in its decor, and the Washington Hilton ordered books by color a while back (“Earth Tones,” he recalled) to place in some of its suites. (General managers at both hotels said they were unfamiliar with the orders, which Roberts said were placed a number of years ago.) Meanwhile, shows at the Kennedy Center have used Books by the Foot’s curations onstage, and sometimes the company’s handiwork even shows up in the homes of politicians.

“We see a lot of them,” Bowman says. “You’ll see in the news they’ll have Books by the Foot [books] in their images in the newspapers, [alongside stories] going inside politicians’ homes and things like that.”

In 2010, NBC’s “Meet the Press” came calling. The show was switching to high definition and debuting a new set with well-stocked bookshelves to commemorate the occasion. Clickspring Design, the firm that designed the set, ordered books on politics, law and an assortment in the style of Books by the Foot’s “Professional Glossy Look.” Bowman remembers the order was for somewhere around 200 feet, or roughly the length of three semitrucks.

Erik Ulfers, founder and president of Clickspring, noted that a good TV set either transports viewers to someplace completely new and unfamiliar (“some are very abstract, really graphic-heavy”) or invites them to someplace welcoming and relatable. He recalls that he wanted the books on the “Meet the Press“ set to project familiarity infused with a sort of intellectual gravitas. He requested vintage books, he says—“It suggests a longer history, and somehow it seems more academic”—and replaced the pages in a number of the books with Styrofoam to avoid overloading the shelves. (When asked about this, Roberts wrote in an email, “As long as books are put in the public eye—and private eyes—they are still part of the culture.” “Meet the Press“ didn’t respond to a request for comment about the order.)

Books by the Foot’s creations have also popped up in a variety of TV shows and movies, many of them politics-adjacent. “Madam Secretary,” “Veep,” “The Blacklist,” “House of Cards,” as well as the 2017 movie Chappaquiddick, for example, have all outfitted their sets with Books by the Foot curations. Some of the most high-profile projects the team works on, however, aren’t revealed to them until after the fact: Bowman has had the distinctly surreal experience of watching a movie for the first time and recognizing her work onscreen. (That’s how it works, she said, with “pretty much anything Marvel.”)

Although TV shows set in Washington underwent a change in tone when Trump was elected (as did much of Washington itself), D.C. residents’ appetites for well-stocked bookshelves, whether as functional libraries or as vanity props, seems to have survived. Or at least, that’s what the demand for Books by the Foot’s services would indicate: The orders Roberts and his staff handled in the Trump years weren’t all that different from the orders they fielded in prior administrations.

To Roberts, though, the unchanging demand is a good thing. One of the positives for a business like his, he wrote in an email, is that familiar types of people, who work in similar fields and likely share similar aspirations, are constantly moving in and out of the area: “Military, [employees of the] State Department and embassies, political folks” are always either settling in or leaving. The imminent changeover to the Biden administration will likely bring precisely the type of new business Books by the Foot has depended on for years.

In 2020, of course, everything changed for Books by the Foot around the same time everything changed for everyone else. For most of the year, the coronavirus pandemic switched up the proportion of Books by the Foot’s commercial to residential projects: In July, Roberts said residential orders, which had previously accounted for 20 percent of business, now accounted for 40 percent. That was partly due to the closures of offices and hotels, Roberts noted—but a few other things were afoot, too.

For one, more people were ordering books with the apparent intent to read them. “We’re seeing an uptick in books by subject, which are usually for personal use,” Roberts said over the summer. Because many people suddenly had extra time at home but hardly anyone was able to shop in brick-and-mortar stores, orders for, say, 10 feet of mysteries, or 3 feet of art books, rose in popularity.

Another force at work, however, was the rise of the well-stocked shelf as a coveted home-office prop. When workplaces went remote and suddenly Zoom allowed co-workers new glimpses into one another’s homes, what New York Times writer Amanda Hess dubbed the “credibility bookcase” became the hot-ticket item. (“For a certain class of people, the home must function not only as a pandemic hunkering nest but also be optimized for presentation to the outside world,” she wrote.) And while Roberts makes an effort not to infer too much about his clients or ask too many questions about their intent, he did notice a very telling micro-trend in orders he was getting from all across the United States.

“We can sort of, you know, guess, or read between the lines, and we’ve had an uptick in smaller quantities,” Roberts said over the summer. “If your typical bookcase is 3 feet wide, and you just want to have the background from your shoulders up, then you might order 9 feet of history, or 9 feet of literature. That way, you put them on your home set … [and] nobody can zoom in on these books and say, Oh my God, he’s reading … you know, something offensive, or tacky. Nothing embarrassing.”

In the fall, Roberts said, numbers evened out somewhat, thanks to some commercial spaces reopening. But Books by the Foot might be taking on a higher percentage of home-library projects well into the future.

Jill Mastrostefano is the creative director and lead designer at PFour, an interior design firm that does, by her estimate, about 75 percent of its business in D.C., Maryland and Virginia. Historically, Mastrostefano mostly has ordered books by color from Books by the Foot, usually to create pops of brightness or accent points in show houses (homes built to display the designs available in a particular subdivision). But this year, she has spent a good chunk of her time outfitting model homes with specific rooms where people can envision themselves taking all their work Zoom meetings.

“We are probably going to be ordering more books because of what are now called ‘Zoom rooms,’ instead of studies,” she says. “People need to, you know, look good when [they’re] on video.”

In Washington and in political circles all over the United States, the fact that people are still, after more than nine months, showing up to work meetings and doing live TV appearances from inside their own homes likely means there will be sustained demand for impressive-looking bookshelves. And given that much of the politics-adjacent workforce won’t go back to working in offices until next summer, Books by the Foot can likely count on consistent Zoom-room business until then.

Of course, there’s evidence to suggest that people want to be or appear well-read but keep Books by the Foot’s involvement hidden. People probably don’t want to talk about their credibility shelves, Roberts points out.

Which has always been, and remains, perfectly fine with him and perfectly fine with Bowman. After assembly in the Wonder Book warehouse, that 12-foot order of left-leaning politics books from August (a somewhat large order for a residential project) was shipped to a private residence in New York for a client whose identity was unknown to Bowman—someone whose use for the books might be revealed one day, or might stay hidden from public view for

The Godfather Coda, The Death of Michael Corleone

From The Polygon:

Francis Ford Coppola’s new cut of Godfather Part III settles the family business for good

A look at what ‘The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone’ salvages

By Jeremy Smith Dec 1, 2020, 9:13am EST

No filmmaker has made better use of the Director’s Cut format than Francis Ford Coppola. Rather than defang and truncate the first two Godfather films for network television in the 1970s, Coppola restructured them as one chronological saga – running seven hours and featuring loads of new footage – that allowed viewers a more straightforward perspective on the Corleone family tragedy. In 2001, Coppola unveiled Apocalypse Now Redux, a massive, meticulously restored expansion of his Vietnam masterpiece that some critics felt eclipsed the already-worshipped theatrical release. And just last year, the filmmaker returned to the catastrophic failure of The Cotton Club for a reworking that, if nothing else, gave the sluggish gangster flick some much-needed musical oomph.

So when Paramount announced earlier this year that Coppola had reworked 1990’s The Godfather Part III as The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, there was reason to hope, based on previous successes, that the director had at last solved some of the trilogy capper’s nagging flaws. But what, realistically, could be done to enhance Sofia Coppola’s awkward performance as Michael’s daughter Mary, or fill the void left by Robert Duvall when he turned down Paramount’s paltry offer to reprise his key role as Corleone family consigliere, Tom Hagen? Coppola may be the maestro of the Director’s Cut, but to fully address these shortcomings he’d have to weave some kind of editorial sorcery that does not yet exist.

What Coppola accomplishes is less a magic act than an elegant threading of a needle. As he states in his introduction to the inelegantly titled The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, the final installment was envisioned as an epilogue to the epic narrative of the first two movies. Indeed, that onerous title was the preferred moniker of both Coppola and The Godfather author Mario Puzo, who partnered with the director on the screenplays for all three films. Paramount understandably balked at the notion of treating the first Godfather movie in 16 years as, in Coppola’s words, a “summation” instead of an event, but by releasing it as “The Godfather Part III” (on Christmas Day, no less), they were priming audiences and critics for a grand finale the filmmaker had no interest in delivering; ergo, much of the initial criticism of the movie, which was rushed through production to meet that prestigious release date, hammered the film for a slow-to-develop plot that felt like a retread of its immaculate predecessors. The narrative familiarity wasn’t viewed as intentional, but rather as a sign of creative bankruptcy.

Coppola’s revision, which runs a shorter 157 minutes, resets expectations immediately by placing its subtitle not only in quotations, but separate from the classic Godfather marionette logo (a first for the series). The opening images of the flooded Corleone compound in Lake Tahoe have been replaced with a low-angle exterior shot of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, an architectural, midtown antiquity dwarfed by its neighboring skyscrapers – which is jarring given that the original The Godfather Part III kicks off in Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral downtown in Little Italy. What’s going on here? Coppola cuts directly to Michael’s meeting with Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly), the overwhelmed, chain-smoking head of the Vatican Bank who desperately sells off the Vatican’s controlling shares in real estate conglomerate Internazionale Immobiliare to the Corleone family. Previously, this scene landed after the Vatican-sponsored ceremony and party feting Michael for his charitable works. By repositioning the Gilday scene, Coppola makes the stakes startlingly clear: Michael is leveraging the Catholic Church’s debt to legitimize the Corleone family business and, not for nothing, become one of the wealthiest men in the world. As the deal is all but consummated, Gilday sheepishly laments, “It seems in today’s world, the power to absolve debt is greater than the power to forgive.” To which Michael retorts, “Never underestimate the power of forgiveness.”

Forgiveness. This is the dramatic business Coppola and Puzo have chosen for Michael in this “coda,” and the film’s busy plotting finally serves a unified theme. Ever since he volunteered to assassinate Sollozzo and McCluskey, Michael has treated life as a chessboard; he sacrificed his own brother to checkmate Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg), and accepted the abhorrence of his wife, Kay (Diane Keaton), as collateral damage. According to Peter Biskind’s The Godfather Companion, Coppola referred to the final shot of The Godfather Part II, wherein Michael sits in silence outside the Tahoe compound, as “the Hitler scene”. He’s not only settled all family debts; he’s severed himself from any semblance of a loving family. He is devoid of humanity. Twenty years later, as Michael enters the final act of his life, he desires expiation. For a man who has done so much evil, this seems an impossible ask. But viewers retain vivid memories of the man who once said, “That’s my family, Kay; it’s not me.” He had other plans. Could there possibly be a path to redemption for this self-made monster?

From Aeschylus to Shakespeare to Arthur Miller, the answer has always been an emphatic “No.” But like all great tragedians, Coppola coaxes his audience into believing there exists a catharsis that could cleanse Michael of his sins and restore the family he brushed aside. The passage of time does a lot of work in the film, and raises many questions: If the Corleone family is successful enough to buy a controlling share in the real estate company Immobiliare, what were they up to in the 1960s — i.e. the decade that sparked America’s fascination with the mafia (and inspired a bestselling book titled The Godfather)? What kind of heat came down on the organization after the assassination of JFK? Did they really avoid the lucrative drug trade that flourished throughout the Vietnam War and beyond?

The Michael of The Godfather, Coda has compartmentalized his business misdeeds. He’s oddly jocular. The Immobiliare deal is complete, pending the formality of the Pope’s approval. He’s a generation removed from his father’s Little Italy territory — now run by the John Gotti-esque Joey Zasa — and he has a savvy publicist (Don Novello) to handle all thorny press inquiries. He is virtually untouchable.

The business may be settled, but for Michael, a man of ultimate conquest, the personal must be confronted. This pursuit was clouded in the film’s previous incarnations, but, by leading with that Gilday scene (instead of the ceremony at the church, which has been excised entirely), it’s the solitary narrative thrust of The Godfather, Coda. Michael isn’t joking about “the power of forgiveness”. He believes atonement is possible. He believes he can reunite his family. He begrudgingly sanctions Anthony Jr.’s opera career, and entrusts the Corleone Foundation to Mary. Kay wants no part of this, but Michael, in a newfound show of vulnerability, allows her to exit a room on her own rather than shut her out. This constitutes growth on the Don’s behalf. As the action moves to Sicily, Michael pours on the charm. He whisks Kay off on a tour of his family’s home village, and summons the memory of the man she once loved (a man viewers barely glimpsed in the first movie). It almost works. It helps that Michael has hedged his bets. Though he’d be thrilled if Kay remarried him, he’ll settle for her not dreading him anymore. The latter appears to be negotiable.

When the Pope’s health goes south, the Immobiliare deal appears to be renegotiable, which places Michael at an unexpected disadvantage as he nears his goal of respectability. Michael expected the “legitimate” business world to be less ruthless than the criminal underworld, but, as he confesses to Connie, “The higher I go, the crookeder it becomes.” It’s an inversion of the naiveté evinced by Kay in The Godfather when she asserted senators and presidents don’t have men killed. Michael’s in over his head, and when he sees the sharks circling he has no choice but to hit back in an old school fashion. To do so, he must cede control of the family to his nephew Vincent (Andy Garcia), and hope for the best. But even if he succeeds, he now knows “legitimacy” is an illusion.

Those hoping for The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone to be a revelation on the level of Apocalypse Now Redux, or a springboard to a fourth chapter in the saga, will be disappointed. There are no surprises beyond the first 20 minutes of this version, save for the denouement, which denies Michael the release of death he received at the end of the previous cuts. His punishment is a long life (“cent’anni”), the very thing he stole from his enemies and, via one unforgivable act, his brother. Sofia Coppola’s infamous performance is what it is; she does the best with what she’s given, which isn’t very much. And that’s the unfixable element of this film. The pieces are there. Coppola and Puzo plotted it out sensibly. But Mary, whose death is meant to break our heart, never registers as more than a frightened child. In a way, this makes sense: she’s been lied to her entire life, and is romantically fixated on her cousin. This is grist for a psychological drama, and there are moments when The Godfather, Coda takes on the intimate grandeur of Luchino Visconti’s Sicilian family drama, The Leopard.

But this is Michael’s story. Mary is what happens when a father projects a false sense of principle. She is sheltered and, as an adult, helpless – incapable of navigating a world that is cruel beyond conception. In this sense, Coppola has mended the movie. The coda is a perfect summation of his twin masterpieces. It is an American tale. And it is finished.

A Pictorial Tribute to Star Wars…

A Pictorial Tribute to 45 Actors & Actresses Who Brought the Skywalker Saga to Life…

Note: I do not own the copyrights to these photographs or the music. I am merely using the photos and music for entertainment purposes.

The complete All the Trailers video collection can be found on this PAGE.

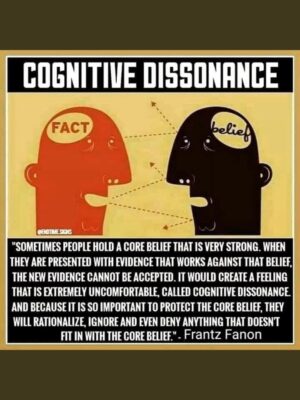

Cognitive Dissonance